This post, which is now archived on the decentralized Scorum blockchain, is in reply to a comment by Joseph S. Salemi that was posted on May 13, 2022 in the comments section of Brian Yapko's ‘In Honor of Birthing Person’s Day’ , that was published by The Society of Classical Poets.

I commend you on having found that needle of a line in Shakespeare’s haystack.

What more can be said in reply to that, other than the words of a devil’s advocate?

Yes, th’argument that thou hast put forth is logical. However, not everything about th’English language is logical! Some things about it are quite silly, many of which are mentioned in “The Chaos” (1920) by Gerard Nolst Trenité.

Speaking of silly, is it not remarkably silly for a line by Shakespeare, whose publications during his lifetime that he himself might not have supervised, to be cited as a solid example of grammatical correctness? Is it not possible that “thy orizons” in the earliest known copies of Hamlet is an error by its earliest actors, editors, or printers, and that “thy orisons” is an error of its later editors?

It is not as though there is a known handwritten manuscript of Hamlet that Shakespeare himself did scribe. It is not as though he had the modern day opportunity of self-publishing his plays and poems onto a decentralized blockchain, such as Hive, Blurt, Steem, or Scorum, or the IPFS (InterPlanetary File System), or Filecoin, whose ledger is near to impossible to cancel, censor, change, or delete.

“What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas”. Likewise, whatever is posted onto a decentralized blockchain stays on that decentralized blockchain.

In part for the sake of posterity (since it is a pernicious practice of Left supremacist programming for all non-Leftist literature to be canceled, censored, changed, or deleted from the internet), I hope for The Society of Classical Poets to consider the importance of mirroring onto decentralized blockchains the content it publishes and has published.

As for what has survived of Hamlet since the days of Shakespeare, when you mentioned “Nymph, in thy orisons be all my sins remembered”, you cited a modern day copy of Hamlet, rather than any of its earliest known copies.

Regarding the earliest known copies of Hamlet, their facsimiles reveal that line has almost as many variants as Fauci’s Frankenvirus:

Quarto 1 (1603) *note: I was not able to find a facsimile of its page that allegedly features this line:

“Lady in thy orizons, be all my ſinnes remembred.”

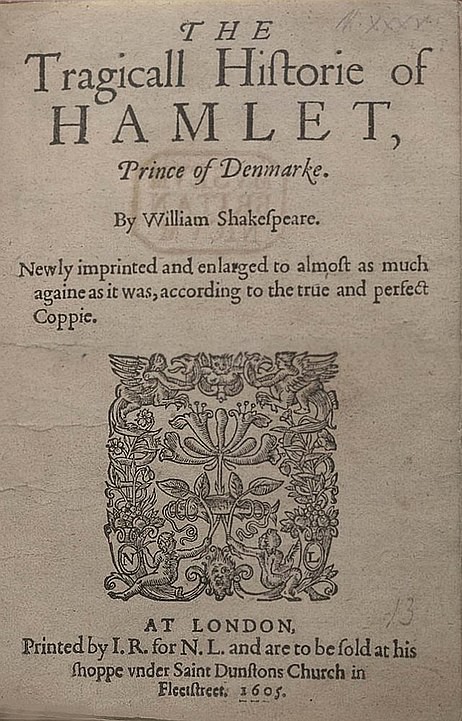

Quarto 2 (1604):

“The faire Ophelia, Nimph, in thy orizons”

First Folio (1623):

“The faire Ophelia ? Nimph, in thy Orizons”

Second Folio (1632):

“The faire Ophelia? Nimph, in thy Horizons”

Third Folio (1663)

“The fair Ophelia ? Nymph, in thy Horizons”

Fourth Folio (1685):

“The fair Ophelia ? Nymph, in thy Horizons”

That line is not exactly the same in any of the first five of the six earliest known copies of Hamlet.

Furthermore, the words “orison” and “horizon” are not even the same word with the same meaning, let alone with the same accentuation.

Yes, “orisons” rather than “orizons, Orizons, or Horizons” is a logical modern day speculation, but it is a stubborn fact that not one of the six earliest known copies of Hamlet features “oriſons” or “orisons” in that line.

An example of Shakespeare specifically having used “oriſons”, rather than “orizons” appears in the earliest copies of Henry V, Act 2, Scene 2:

Quarto 1 (1603):

“Alas, your too much care and loue of me

Are heauy oriſons gainſt the poore wretch,”

First Folio (1623):

“Alas, your too much loue and care of me,

Are heauy Oriſons ’gainſt this poore wretch:”

Second Folio (1632):

“Alas, your too much love and care of me,

Are heavie Oriſons ’gainſt this poore wretch :”

Third Folio (1663):

“Alas, your too much love and care of me,

Are heavy Oriſons ’gain’ſt this poor wretch :”

Fourth Folio (1685):

“Alas, your too much love and care of me,

Are heavie Oriſons ’gainſt this poor wretch :”

I put forth the argument that the Quartos and Folios show that “orisons” being used in modern day copies of Hamlet is an error. If Shakespeare meant to have used “orisons” then why didn’t he use “oriſons” as he did in Henry V? Because he made a spelling mistake? If he made a spelling mistake, then why shouldn't it be surmised that he also made a grammatical mistake in his having used "thy" rather than "thine"?

Because that line in the earliest copies of Hamlet was altered so many times (with not one of them having changed “orizons” to “oriſons” or “orisons”), and because every dictionary defines “thine” as being used instead of "thy" when "thy" is placed before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h, it begs the question: Did that line in Hamlet as Shakespeare originally wrote it actually feature “thine” rather than “thy”? Was it changed from "thine" to "thy" by its earliest actors, editors, or printers?

It is for more than one reason that the line in question from Shakespeare’s Hamlet is as problematic as a ballot from the 2020 U.S. presidential election! I accuse it of being ineligible to be cited as a solid example of grammatical correctness!

As for "thy" and "my", it is a fact that every dictionary defines both “thine” and “mine” as being used instead of “thy” or “my”, whenever “thy” or “my” is placed before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h.

Yes, it is also a fact that modernists use “my” before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h.

But that does not necessarily mean it is kosher for classicists when using “thy”, which is an archaic word, to have it remain as “thy” if placed before a word whose first letter begins with a vowel or h.

Yes, it would be logical to do so, but logic is not necessarily the name of the game when observing the English language, as every dictionary also defines the plural of “goose” as “geese” and the plural of “moose” as...“moose”!

What a silly language the English language sometimes is!

If changing the definition of “thy” whereby it can be used before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h, then why not also change the plural of “moose” to “meese”?

A key difference between “thy” and “my”, is that the former is always accented, whereas the latter is not necessarily accented. If it is now kosher for classicists to use “thy” before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h, then why shouldn’t “thy” be further changed whereby, like “my”, it also does not necessarily have to be accented?

If so, then why shouldn't every dictionary also change "mother" to "impregnated person"? Where does the Left supremacist narrative of Language Change end—when all humans have become mute, as portrayed in the original Planet of the Apes movie?

Besides Shakespeare’s Hamlet, do you happen to know of any examples where a classical playwright or poet of antiquity who supervised the publication of their work used “thy” before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h?

Also, do you happen to know of any examples from antiquity where a writer used "my" in the modern manner by means of their having placing it before a word that begins with a vowel or h? Did Shakespeare himself do that?

When Brian wrote “To ever honor thy Impregnating Person”, was that actually an example of grammatical correctness, or was it really an example of him having exercised his poetic licence? Was he being objective or subjective? Was he being serious or silly?

It might be that the argument you put forth is an objective argument. But without there being additional evidence presented that shows one or more classicists of antiquity who supervised the publication of their work having used “thy” before a word whose first letter is a vowel or h, it is a speculative argument that might also turn out to be a silly argument if we are using the greatest English language writers in history as our guide.

Comments