Many are accustomed to believing that medieval medicine is a complete charlatanism and then one should not hope for reasonable treatment. In fact, the doctors of that time knew how to do something...

The life of a medieval soldier is easy to reconstruct. More or less complete samples of weapons and equipment have come down to us, descriptions of some everyday moments, images of clothes (and the things themselves are found in museums), treatises on fencing, historical chronicles, account statements ... It's all troublesome to put together, but not like that it's impossible. It is much more difficult to reconstruct or imagine the fate of a wounded soldier, because here we are entering the shaky ground of our own prejudices. Since it is generally accepted that unsanitary conditions and religious obscurantism, obligatory for the Middle Ages, should cast their ominous shadows on this sphere, so almost any serious injury at a time when standing urine and prayer were considered the most effective medicines meant inevitable death. But the facts say otherwise.

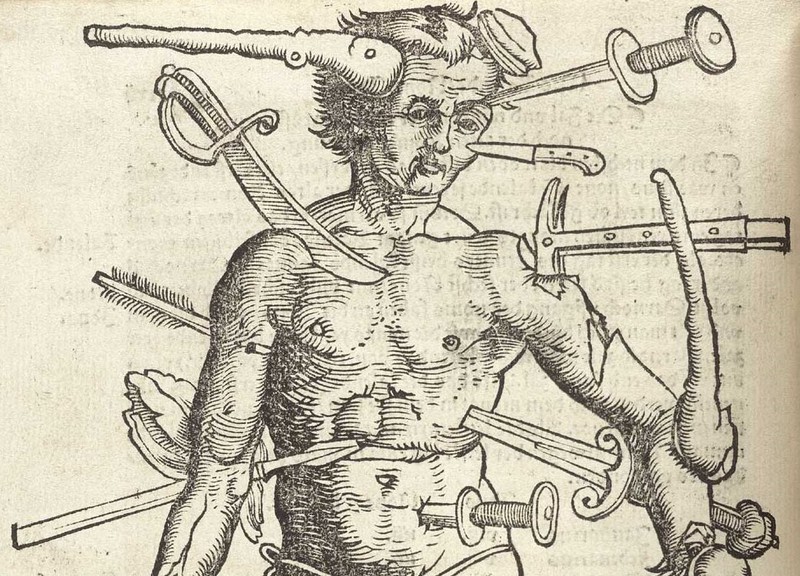

A careful study of soldiers' graves after major battles paints an interesting picture. Yes, it is not possible to examine soft tissues (they simply decayed), and traces on the bones do not remain after every injury. And yet. It turned out that in the era of the dominance of edged weapons, the main wounds were on the head. In terms of mass, they were inferior to lesions of the limbs. But the rest of the person got absolutely nothing - which is understandable and understandable. Firstly, they tried to pack the body in armor and it was difficult to get to it. Secondly, a blow to the head is much more reliable incapacitating the enemy than hitting the torso. Well, the wound of the arms and legs is also easy to explain - before we hit the enemy on the skull, it would be nice to make him stop waving dangerous pieces of iron or redirect him out of order to the stalls - it’s easier to deal with him. Why were they beaten on the legs or arms.

And yet, between 25 and 30 percent of medieval battle victims retained the marks of former, already healed injuries on their bones. And these wounds, at times, were very serious. Here are the fused bones of the arms and legs (not always evenly), and the tightened holes in the skulls, and even severed cheekbones and jaws - these marks, presumably, did not add to the appearance of their owners. But the fact remains - a person was able to survive after such blows, managed to recover and even found the strength to participate in other battles. Consequently, one fasting and prayer during his treatment did not work. Yes, the legacy of Galen in the Middle Ages was lost somewhere, but some knowledge was still available.

The combined study of written sources and archaeological materials gave scientists a detailed understanding of the issue. Military field medicine at that time was imperfect, but it was. And the patient's survival depended on the nature of the injury and the affected area, but in general it was on top. Which is largely due to the relative "safety" of the weapons of that time - not so much dirt got into the wound, as happens with a gunshot wound. Although there were features here too - stab wounds from the sword threatened to a lesser extent with sepsis than blows from a spear or arrow.

It is estimated that approximately 90 percent of abdominal wounds at that time ended in failure. All because of the same infections. Approximately 60 percent of chest wounds had the same ending. But the wounds of the arms, legs and head already gave an impressive picture of healing - about 70 percent of the victims returned to duty!

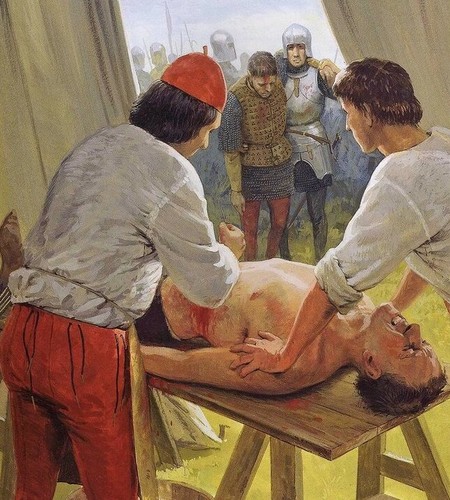

So what methods have helped? Crushing lesions of the limbs and fractures (sometimes very complex) were treated in much the same way as now - they ensured the immobility of the limb with the help of a splint or splint. With a tight bandage combination. Stab and cut wounds were treated with wine or vinegar (antiseptic) and pulled together with sutures. Moreover, the need for drainage of purulent wounds was understood even then. Also, if necessary, hemostatic tourniquets made of skin were widely used, and in some cases, bleeding was quickly stopped by cauterization with oil or iron. Well, it’s difficult to call the tools of the then doctor primitive - just remember the device with which they removed the arrowhead from the facial bone of an English prince ...

Herbs with astringent and anti-inflammatory properties were well known at that time. And even anesthetics were regularly used (mainly based on opium poppy or belladonna), although it cannot be said that it always ended successfully for the patient - they could have made a big mistake with dosages. And yet the fact is that they used it. Apparently, quite widely, as evidenced by both medical writings and studies of the cesspools of knightly hospitals.

It is interesting that Europeans adopted a lot from Eastern doctors during the time of the Crusades. At that time, the Saracen healers had much more advanced knowledge than their European counterparts. In particular, the crusaders adopted the practice of a special healing and strengthening diet from the Arabs, which included dried fruits, nuts and meat, regardless of the presence of religious prohibitions - the prayer of a drunk and fasting of a sick person, as you know, do not reach God. From there, the desire to maintain cleanliness around the wound and the regular change of breathable dressings - earlier relied more and more on bloodletting and humility of the flesh. In fact, ancient medical knowledge was preserved in the east. And during the Crusades, they were re-exported.

In any case, the wounded in a medieval battle, if he was not trampled in the heat of a fight and managed to survive the blood loss, reaching the moment of collecting the victims, which was not very hasty, there was a good chance of surviving. The picture will change dramatically in the era of firearms. It is not surprising that gunpowder was at first perceived as a diabolical invention. And the point here is not only in the smell of sulfur, but in a completely different nature of wounds, which they did not immediately learn to treat.

Comments